Grown-ups are giving up books. Should we pay them to read?

Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

Australia, which is undergoing one of the sharpest declines in reading in the developed world, is one of the countries doing least about it.

We spend a lot of time worrying about how much or how little children are reading, yet the most alarming signs of decline are among adults. The older we are, the more we read – yet since 2019, the older we are, the faster we are giving up reading. Something is happening to the mature mind in this country, and we are nowhere near reckoning with it.

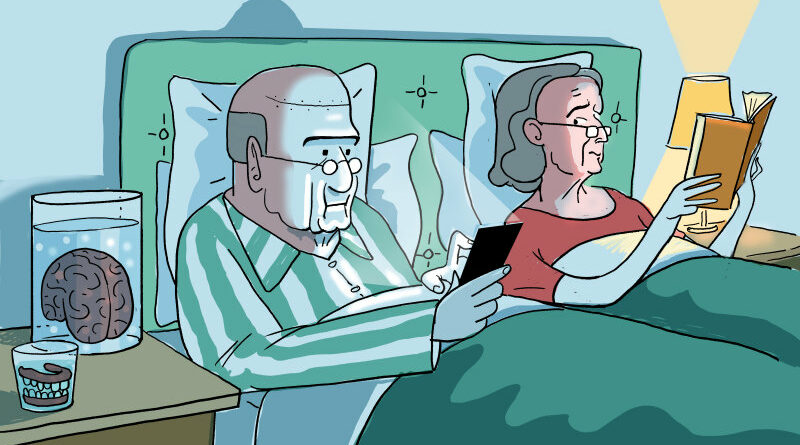

Credit: Simon Letch

According to the latest National Arts Participation Survey, older Australians reading books for pleasure has fallen from 77 per cent to 68 per cent in the last five years. That is measured by reading just one book a year. It mightn’t sound like a lot, but it is the biggest decrease ever recorded in such surveys. A third of retirement-age Australians now never read a book at all, up from a quarter just three years ago.

The suddenness of the change is producing anxiety in the book industry, where a fall in

sales volumes accompanied by a spike in paper prices is already leading to job losses and

other cutbacks. The slump indicates something fundamental, a shift in the inclination and

ability of older Australians, the heart of the book-buying population, to focus.

We fret about how mobile devices are slicing and dicing young people’s minds. I was told this week that in primary schools, given a big sheet of paper to draw a picture on, students increasingly choose to draw pictures the size of their mobile device screen. The very scope of the human eye is changing before us. Yet while educators rally and devote resources to enlarging the mind of a child, what is being done for those who have long left the pedagogical nest, who are subject to the same changes in the way they see and the way they think?

You don’t need to travel far to hear older Australians confessing that they are simply less able to concentrate. Those who once propped up the book trade with their late-night reading are now swiping themselves to a fitful sleep on their mobile devices, filleting their ability to focus for longer periods on longer narratives. Kids, who still have to read books at school, are the most attended-to of our poor concentrators. It’s adults we should be thinking about helping.

When it comes to literacy, Australian government research has found that 44 per cent of mature adults read at year 10 level or lower. Eighty-two per cent of the adult population reads at year 12 or lower literacy. This is Australia in 2023. Is it any wonder that public debate is an exchange of simplifications, that politicians draw verbal pictures in crayon? This is what we are; this is what our brains take in.

The decline in reading and literacy is not a local trend, but Australia is among the countries doing least about it. Germany has recently become the latest European country to offer a mind-expanding incentive to every person turning 18. From this year, coming of age in Germany is celebrated with a 200-euro ($334) “culture pass”, a voucher from the government to spend on cultural products. Valid for two years, the pass can be spent on theatre, music, film, books – it’s up to the 18-year-old to decide how. By any measure, it makes economic sense: it invests one euro for every 700 euros the cultural and creative industries return to the German people.

Germany is not the first. Italy, France and Spain have introduced similar vouchers for 18-year-olds, worth up to 500 euros. Responding to fears that teens would only spend the money on video games and music downloads, higher caps are placed on the pass for cultural events deemed more worthwhile. For example, Spanish 18-year-olds can only spend 100 euros on digital media, but up to 200 euros on live events and physical artefacts such as books.

The result, perhaps unexpectedly, has seen up to 75 per cent of the French vouchers spent on books. Japanese manga publishers have been the biggest beneficiaries, but those school-leavers are at least reading something. Manga today, Proust tomorrow! Maybe next year. The purpose in the short term is to counter the threat to the existence of cultural industries; in the long term it is to restore adults’ endangered ability to concentrate.

I’ve done the maths on this. About 310,000 Australians turn 18 this year. Give them each a $200 culture pass and the cost is $62 million. How much is that? It’s one-322nd of what the government will hand back in its stage 3 tax cuts. You could provide this voucher every year for the next 6000 years before it reaches the price of those nuclear subs.

Australians value our culture, both economically and otherwise. Cultural and creative industries contribute $122 billion to our economy. In the National Arts Participation Survey, overwhelming majorities of Australians said the arts contributed positively to their ability to express themselves, to stimulate their minds, to help them devise new ideas, to deal with stress, anxiety and depression, and to increase their well-being and happiness. The older we get, the more we recognise this value in our lives.

Yet we have no parallel to the UK government’s Reading Well program, which spends £7.5 million ($14.4 million) on ensuring that any book recommended by a doctor for health purposes is made available to patients for free. Access to books allows the UK to spend pennies to save pounds.

So here’s another idea. Australians aged 65 and over have always been our biggest readers. Yet the drop-off in reading is occurring fastest in that age group. Thirty-five per cent of older Australians now never read a book at all, compared with 25 per cent in 2019, the biggest recent change in reading habits in any demographic.

So why not give everyone turning 65 a $100 book voucher? It would cost the federal budget $28 million, which is one dollar for every $414 the Commonwealth currently spends on, for example, mental health services. Or put another, private-sector way: in 2022, two older Australians, Gina Rinehart or Andrew Forrest, each increased their wealth by $28 million every three days.

We’re living longer. It’s not just children whose ability to concentrate needs nurturing, and it’s not just children who will turn their brains to mush if they don’t get off their flipping devices. It’s not just children who are the mental powerhouse of the next century. Those 65-year-olds have still got another two to three decades to either use or lose their minds. They have a lengthening future; there is more than one way of saving it.

Malcolm Knox is an author and regular columnist.

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from books editor Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article