Mrs Simpson's calamitous visit to Balmoral that outraged the royals…

When Wallis came to Balmoral! How Mrs Simpson’s calamitous visit and triple-decker toasted sandwiches outraged the royals. And set the clock running to the Abdication Crisis…

- Edward VIII brought his mistress along in 1936 and abandoned old traditions

- She had no time for tweedy clothes, game pie or Scottish reels

- For all the latest Royal news, pictures and videos click here

If there’s one place that can be associated with happiness for the Royal Family, it is Balmoral.

Ever since it was first purchased by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, for whom it served as a poignant reminder of the rural Germany of his youth, it has been a place that offers privacy, rest, stunning scenery, and a chance to spend time together as a family.

A photograph taken by Sophie, then Duchess of Wessex, of the late Queen and Prince Philip, smiling and relaxing together amid the heather sums up Balmoral’s pleasures.

King Charles began his own poignant stay at the castle yesterday – a visit that will include the first anniversary of his mother’s death there.

The ate Queen and Prince Philip in Scotland on the Balmoral Estate in 2003. Balmoral has been one of the very happiest places for the Royal Family

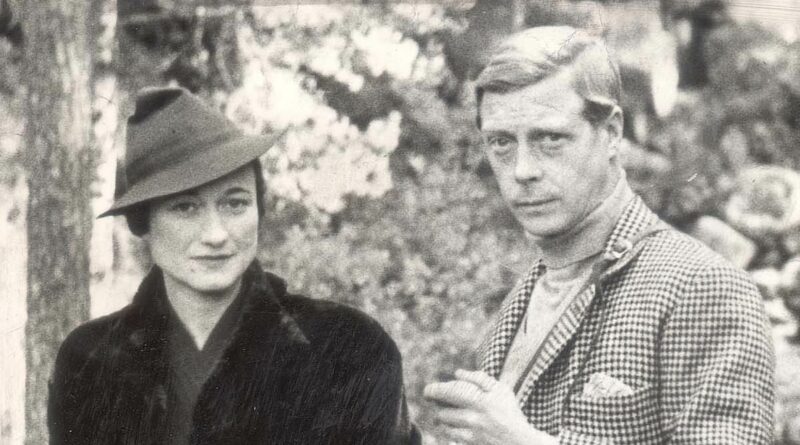

King Edward with Wallis Simpson at Balmoral in 1936. It would prove to be a calamitous stay. Not only was Wallis still married, she was already a divorcee

King Charles inspects the Royal Regiment of Scotland yesterday, as he begins this year’s stay at Balmoral. Coming up to the first anniversary of his mother’s death, it will be especially poignant

Edward VIII, far left, pictured on the 1936 Balmoral visit. Wallis is third from the right

But for one monarch, Balmoral would lose its charm.

Edward VIII spent two weeks of his late summer holiday there in 1936, together with the woman for whom he would give up the throne. It did not go well.

Edward VIII and Wallis Simpson abandoned many of the family’s Balmoral traditions and outraged his royal relatives.

Official duties were ignored, as were important guests. Edward preferred to be surrounded by his chums. Wallis acted as if she were the hostess, planning the meals and entertainment, yet was neither married to the king nor divorced from her current husband.

The drama of that summer in Scotland was in many ways the starting point of Edward’s abdication, three months later. According to diarist Chips Channon, the visit was a calamity

Edward’s Balmoral sojourn came in September, eight months after he had acceded to the throne following the death of his father, George V, in January 1936.

He had first met Wallis Simpson in 1931 and some historians suggest she had replaced Edward’s previous lovers, Lady Furness and Freda Dudley Ward by 1934.

READ MORE: How the Queen Mother’s snub to Wallis Simpson at the Scottish estate proved she would NEVER be accepted by the royal family

In the summer of 1936, now King, Edward took Wallis on a cruise of the Adriatic

Could Edward really have thought that he could marry the twice-divorced Wallis, make her Queen, and be crowned as King, Defender of the Faith and Supreme Governor of the Church of England?

In August, there were other clouds on the holidaying couple’s horizon. The Foreign Office intervened, warning the King to keep away from the south of France because of its proximity to the Spanish Civil War, and from Venice because of Mussolini, so they finally sailed from the Adriatic to the Bosphorous.

The couple were photographed everywhere they went, with Wallis convinced that their love affair was popular with what she called ‘uncomplicated people’, who cheered them on the harbour sides.

Balmoral, in the highlands, was purchased by Prince Albert and is a place of great family importance to the Windsors. Wallis Simpson’s visit was not a success…

King Edward VIII, centre, inspects the troops at Balmoral on the fateful 1936 visit. He is accompanied by the Duke of York, later King George VI, father to Queen Elizabeth

Edward and Wallis , centre, with friend Katherine Rogers during their Adriatic cruise in the summer of 1936, just before their visit to Balmoral. Wallis is wearing a bracelet with Cartier crosses on her left wrist – a gift from Edward. He had matching Cartier crosses, which he wore on a necklace

Princess Elizabeth rides by the side of her uncle David, as he was known in the family, on a 1933 visit to Balmoral

The Duke and Duchess of York in the Balmoral rock garden with Queen Mary in 1924

By September 14, the cruise came to an end, with Wallis staying in Paris and the King flying to London from Zurich before going on to Balmoral.

He fully expected Wallis to join him, but she then succumbed to enormous doubts about their future when she read newspaper accounts about their relationship while she was in Paris.

She wrote to the King, telling him that ‘I really must return to Ernest….We have had lovely beautiful times together and I thank God for them and know that you will go on with your job doing it better and in a more dignified manner each year. That would please me so. I am sure you and I would only create disaster together.’

Edward would not countenance losing Wallis and through phone calls and letters wore her down until she agreed to join him at Balmoral. She also pressed ahead with plans for the divorce, meeting Goddard in London before travelling to Scotland to be with the King.

Edward loved the Highlands of Scotland and wrote to friends of its attractions: deerstalking, grouse-shooting, fresh air and exercise. But, as he wrote later in his memoir, A King’s Story, ‘I had sometimes found the transplanted routine of the Court at Balmoral a trifle too formal for my tastes’.

It had become traditional for politicians, including the Prime Minister, to stay with the monarch there, as well as senior church figures. Edward was having none of it.

He decided to confine what he called ‘my first house party there as King’ to people he found fun – Wallis and his American friend and golf partner, Herman Rogers and his wife Katherine, together with Esmond Harmsworth, later the second Viscount Rothermere, and Louis and Edwina Mountbatten.

It is usual for the Royal Family, although on holiday at Balmoral, to undertake some engagements in Scotland during their stay. But that summer, Edward was having none of that, either.

He had been invited to open the Aberdeen Infirmary and wrote to the Lord Provost of Aberdeen to decline, saying that the court was still in mourning for his father, George V.

This somehow did not stop him from asking his brother, the Duke of York – later George VI – from deputising for him.

The Duke and Duchess of York were staying some miles from the main house at Balmoral, at Birkhall – the house that would first become a summer home to the Duchess, later Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, during her widowhood and then to Prince Charles, now King.

That summer, the Duchess of York wrote to George V’s widow, Queen Mary, about the King’s request that she and her husband deputise for him in Aberdeen, clearly thinking that it would have been better if her brother-in-law opened the hospital himself.

Then she mentions Mrs Simpson in her letter, but clearly cannot bring herself to name her: ‘I am secretly rather dreading next week, but I haven’t heard if a certain person is coming or not – I do hope not as everything is talked of up here.’

The Duchess’s fears were hardly groundless, for on the very day, September 23, that she and the Duke travelled to Aberdeen to open the hospital, Edward drove to the city too – but to collect Mrs Simpson from the train, and avoid her having to get the branch line to Balmoral.

Despite his motoring goggles, he was recognised and later the evening paper displayed two photographs on its front page: one of the Duke and Duchess at the hospital, and the other of the King, meeting his guests at the station.

It was a powerful symbol of what was to come some months later with the abdication: the Yorks stepping into the breach and fulfilling duty, because Edward opted to be with Mrs Simpson.

Prince Edward, right, pictured at Balmoral in 2010 with younger brother Bertie, as he was known (later George VI) and sister Princess Mary

The young Queen Mother as the Duchess of York standing with Her Majesty Queen Mary at Balmoral Castle in September 1923

The future Queen Elizabeth II with Queen Mary, left, and the Duchess of York at Balmoral in 1927

The Aberdeen incident caused tongues to wag and courtiers to fret. The courtiers – and London society – then noticed that when the Court Circular was published, the King ensured that Wallis Simpson was listed ahead of the Duke and Duchess of York (the future King and Queen!).

Tommy Lascelles, the courtier who would go on to serve George VI and his daughter, Elizabeth II, as private secretary, wrote disparagingly of Edward: ‘He had no real friends for whom he gave a straw. His private secretaries had a devil of a time’.

The Yorks were furious, feeling they had been made to look as if they condoned the King’s actions. Back at Birkhall, they may well have found a sympathetic ear: they had asked Cosmo Lang, the Archbishop of Canterbury to stay after he had not been invited to Balmoral by the King.

He and Edward never got on and Edward had declined to meet him to discuss his Coronation. Lang, meanwhile, recorded his thoughts about his stay at Birkhall, commenting on the Yorks’ elder daughter: ‘Strange to think of the destiny which may be awaiting the little Elizabeth at present second from the throne’.

Despite their distress about Aberdeen the Yorks accepted an invitation from Edward to attend a dinner at Balmoral. There, Wallis was planning the meals and the evening entertainments. But the invitation only caused more strain between the two couples.

The author Michael Thornton reconstructed the evening from the evidence of someone who had the event described to them by someone who was there.

Wallis acted as if the hostess, despite being married to someone other than the King at the time, and stepped forward to greet the Yorks.

The Duchess swept past her, saying loudly, ‘I came to dine with the King’.

The Queen Mother’s official biographer, Wiliam Shawcross, quoted from a letter that the Duchess of York, clearly upset, sent to Queen Mary, which underscored the extent to which being divorced, as Wallis already was from husband number one, put people beyond the pale in 1936.

‘I feel that the whole difficulty is a certain person,’ wrote the Duchess, ‘I do not feel that I can make advances to her & ask her to our house, as I imagine would be liked, and this fact is bound to make relations a little difficult….the whole situation is complicated and horrible and I feel so unhappy about it sometimes.’

But there is also a small hint of personal animosity; perhaps the Duchess of York knew that Wallis was as much a snob in her own way as London high society, and looked down on the Duchess as unsophisticated as a Scottish cook, calling her Cookie to Edward.

The relationship between Elizabeth, Duchess of York and the King had definitely become strained; once a letter starting ‘Darling David’, as she had long called him, would have been appreciated. Now it became mocked as cloying.

While the British public remained in the dark about what was afoot in the world of their new King, people in public life were forming their own views.

Chips Channon, the diarist, thought the Balmoral stay was a turning point in the fortunes of the couple. ‘The visit to Balmoral was a calamity’, he wrote, ‘after the King chucked opening the Aberdeen Infirmary, and then openly appeared at the station on the same day, to welcome Wallis to the Highlands. Aberdeen will never forgive him’.

Winston Churchill, who had been somewhat sympathetic to the King at first, saying that he thought Mrs Simpson was not affecting his performance as King, considered it a mistake to have her at Balmoral, which was sacred to the memory of Queen Victoria.

The castle, seen from a wintery distance. The landscape is said to have reminded Prince Albert of his German home

A portrait of the newly engaged Wallis. The ring features a huge emerald

The first portrait of the couple after their marriage at the Chateau De Cande, in Monts, France, in June 1937. She is wearing the Cartier crosses once again

The Queen was rarely happier than when at Balmoral. Pictured here in 1967

Edward was seemingly not bothered about Queen Victoria or anybody else, for that matter. He gave Wallis the best guest room at the castle and rather than use the usual room for the Sovereign, installed himself in her dressing room. The couple also introduced after-dinner films – very different from the usual evening pastimes at Balmoral such as dancing Scottish reels.

Mrs Simpson also eschewed the usual tweedy garb of the Scottish retreat: on cine film she was captured there in town dress, with smart suits and black felt hats.

Perhaps Mrs Simpson’s greatest innovation – which younger generations of royals, not so keen on a diet of game pies and haunches of venison, might appreciate – was her introduction of triple-decker toasted sandwiches as late night fare. They went down badly with the kitchen staff, already hard-pressed after Edward had made cuts to the numbers employed at Balmoral.

After the King returned to London from Scotland, things moved apace. Both the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin and Archbishop Cosmo Lang had returned from their summer breaks to desks piled high with letters from British citizens abroad, appalled to read in the foreign press about the King and his relationship with Mrs Simpson.

Lang and the King did not get on, and so he and Baldwin, together with other senior public figures, thought the Prime Minister would have to talk to the King about Wallis.

Without initially mentioning Mrs Simpson, Baldwin told the King that ‘since the war …. people expect a higher standard from their King’. He then went on to mention the large amount of letters he had received about Mrs Simpson.

According to Edward’s biographer, Frances Donaldson, he then warned the King: ‘I think you know our people. They’ll tolerate a lot in private life but they will not stand for this kind of thing in the life of a public personage and when they read in the Court Circular of Mrs Simpson’s visit to Balmoral they resented it’.

Baldwin then asked the King if he could have Mrs Simpson’s pending divorce to her second husband put off, but Edward said it was her private business and he could not influence her just because he was her friend – a comment that Baldwin said was the only lie the King ever told him.

But the dam finally burst on December 1.

While the American press continued to be filled with headlines such as King Will Wed Wally, the British papers kept mum – until a bishop let rip.

At an obscure conference, the Bishop of Bradford, Dr Alfred Blunt, commented on the forthcoming coronation and the duties of the King, saying that he was in need of prayer. ‘We hope that he is aware of his need. Some of us wish that he gave more positive signs of such awareness’.

The Duke and Duchess of Windsor in Bermuda on the way to the Bahamas, where they were sent for the duration of the war. She is wearing an extraordinary diamond and cardinal gemstone flamingo – a gift from Edward – on her left lapel

The Press Association report of Blunt’s remarks was enough to open the floodgates of British reporting and comment, and within nine days, Edward gave up his throne and Mrs Simpson had no chance of becoming Queen. Those late summer days at Balmoral, when she was effectively chatelaine of the Royal Family’s holiday home, seemed very far off indeed.

In mid October he had a meeting with the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, and was shocked when the King told him he was determined to marry Wallis Simpson and be her third husband. Baldwin was horrified. Meanwhile, plans continued for the King’s coronation, although he paid little attention and sent the Duke of York in his place to meetings.

By November, the King received a letter from Alexander Hardinge, and from senior ministers warning him that journalists would not keep silent for much longer about his relationship with Mrs Simpson.

Catherine Pepinster is author of Defenders of the Faith – the British Monarchy, Religion and the Coronation.

Source: Read Full Article